Today’s article is a guest post by story and Enneagram expert Jeff Lyons of StoryGeeks.com. His article touches on a often overlooked aspect of story development that many writers miss and their story structure suffers as a result: their main character’s “moral problem”.

Today’s article is a guest post by story and Enneagram expert Jeff Lyons of StoryGeeks.com. His article touches on a often overlooked aspect of story development that many writers miss and their story structure suffers as a result: their main character’s “moral problem”.

Jeff will be teaching us more about how to identify a character’s moral problem in his upcoming workshop here in Berkeley, California (I’m co-hosting) on October 26 and 27 on his method of Rapid Story Development. We’d love to have you join us if you’d like to learn more.

Now here’s Jeff’s article:

![]()

The problem is moral

Hands down, the most important and most overlooked story structure element all writers either miss altogether or bungle is the moral problem. This pesky problem is not just a nice perk — it is a make-it-or-break-it story structure component of any good story.

The moral problem is the hole in the heart of your protagonist. He or she starts off the story in some pickle, some predicament of their own making, ideally brought about by the very moral problem to which they are oblivious. This problem is making them act badly in the world. They are hurting people emotionally, mentally, and maybe even physically due to this lack. It’s the hurting of others that make it a moral issue, and not just a psychological one (the distinction is about hurting others versus hurting oneself). The character needs to learn some lesson about how to live in the world so that they no longer hurt others; some lesson that elevates them (hopefully, but not always) to be a better person. They learn that life lesson that makes them moral again.

Good stories have protagonists with this hole in their heart. And the best stories rip out the protagonist’s heart and then somehow heal it again, before the heart gets put back inside (I’m speaking metaphorically, of course — unless this is a Clive Barker horror story).

How to find the moral problem

So, the question becomes: how does a writer figure out how to find one of these heart-holes? How do you assure that your protagonist has a meaningful moral problem and an equally meaningful growth-moment at the end of the story where they see the error of their evil ways? Some writers have a natural gift for this and flawed and tortured protagonists come to them as gracefully as flight to an eagle. For others (i.e., most of us) the process of finding a good moral problem is more like trying to find a taxi on a rainy night.

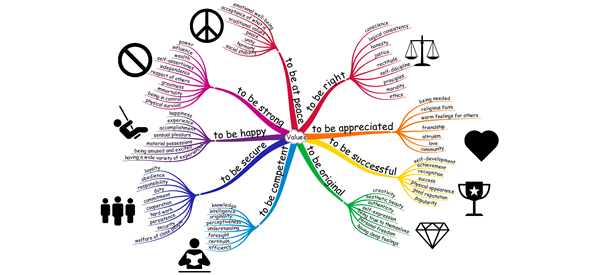

The good news, however, is that there is a tool that any writer can use to help them crack this problem, regardless of their natural gifts. That tool is called the Enneagram. The Enneagram is a powerful archetypal system that describes the nine core personality drives underlying all human behavior. Each of the nine drives is rooted in thoughts, feelings and actions that largely determine how we interact with the world, for good or ill. Everyone has an Enneagram type — including fictional characters and stories themselves. Writers have used this tool for many decades to develop multi-dimensional characters, but it can also be used as a story development too, when coupled with story structure principles. It is this relationship between the Enneagram and story structure that gives writers a doorway to finding the most dramatically powerful moral problem for their protagonist.

What’s your character’s poison?

Let’s take an example and walk through the problem as a point of illustration:

You just wrote the movie The Verdict. Frank, the protagonist, is a ambulance-chasing, alcoholic lawyer who is constantly looking for the next sucker to scam into hiring him. You know he’s a drunk. You know he’s in pain. But what’s his moral problem? Is his alcoholism the moral problem? Alcohol hurts lots of people. Is his pain the moral problem? If so, what’s the pain? How do you figure out which it is? Writers spend lots of time caught up in this maze of questions and confusion.

Enneagram to the rescue. Each of the nine Enneagram personality styles has something called a “poison”. This poison is the hole in the heart. It is the thing that poisons everything they do, everything they feel, everything they think. So, what’s poisoning Frank? Certainly alcohol is, but that’s mostly just hurting him. It’s not hurting other people. What he’s doing that’s hurting others is that he is using them. He sees people as targets, not people. So, we have the answer, right? He’s using people. That’s the moral problem, right? No, not quite. That’s what he’s doing; that’s not why he’s doing it. The moral problem is the motivation, the thing causing the using.

The Enneagram poison can help you quickly answer this question and find the real moral problem. Of the nine personality styles, the 3rd style (“The Achiever”) is the one who has the poison of secretly feeling that they have no personal worth or value. This fits Frank’s actions to a tee. For him, people have no value; they’re things to be used. He ultimately feels this because deep down he believes he has no value or worth himself and therefore no one else has value either. Over the course of the movie he learns that, indeed, not only do people matter, but that he himself matters and he can make a difference in the world.

And so not only does the Enneagram technique of looking for the poison explain the motivation behind the protagonist’s immoral behavior, it also points to the final self-revelation at the end of the story, where the hero or heroine realizes how to heal the hole in their heart. In this case, Frank realizes he has value and so do other people. He is able to make a new choice as a result.

Moral problem and story structure

As a writer, having this key piece of information — a clear moral problem — is critical for you to not only address your main character’s development and arc, but also to guide you on how best to structure your story so that key story beats, like the inciting incident, low point, and final climax, are all driven by the engine of the protagonist’s moral problem.

This is a deep subject, but a critical one for any writer. The moral problem can make or break your story, and the Enneagram can help you rapidly navigate the difficult questions that might otherwise hang you up and drag out the development process.

If you’d like to learn more, join us in Berkeley on October 26 & 27. Early registration ends TOMORROW, Thursday, October 10. Find more and register here: http://RapidStoryDevelopment.com

Your turn

As always, we love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Warmly,

You may also be interested in:

- The Power of the Enneagram

- Using the Enneagram for Story Development

- Constructing a powerful premise line as a framework for story structure

- Using the Enneagram to move from character to story

Thanks for reading.