Today we’re continuing with Part 2 of a two-part article from story consultant Jeff Lyons, author of Anatomy of a Premise Line.*

In the first article, Jeff reviewed the first two steps of the process:

- Step 1: Identify the Core Structure of Your Story

- Step 2: Assess Whether You Have a Story or a Situation

Now he’ll guide us through assembling the building blocks we’ve created into an actual premise line:

- Step 3: Map the Core Structure to the Premise Line Template

- Step 4: Finalize the Premise Line

- Step 5: Test the Premise Line with Objective Readers

Note: Creative nonfiction writers can also benefit from learning these tools, because story is story and biographies, “true stories” and other creative nonfiction all adhere to the same storytelling principles as fiction.

Read the article below, or download our Master Your Premise Line Guidebook here:

![]()

Five Essential Steps to Crafting Your Premise Line, Part II

by Jeff Lyons

Now that you’ve identified the core structure of your story, and assessed whether you have a story or a situation (and made any necessary adjustments to your situation if so desired), you can continue on to Step 3, mapping the core structure to the premise line template. And if you’re still still unsure whether you have a story or a situation, you can use the premise line template as your key to unlock this mystery.

Step 3: Map the Core Structure to the Premise Line Template

This template takes a very specific form of four clauses (this draws on basic grammar, we’re simply using the clauses that make up sentences). Mapping the core structure elements identified in step one to this template will quickly tell you if you have a workable story.

Let’s breakdown each clause into its constituent parts to see the true power it offers your writing process.

![]()

Clause #1: Protagonist Clause

Take your sense of the first two components of the Core Structure (character and constriction) and combine them into a sentence clause (the structure components are in bold).

You have a sense of a character. Now is the time to give them some dimension. Who are they? What takes them from a state of just being and sparks them into action? Some call this the inciting incident; maybe you don’t have that clearly in your head yet, that’s okay. What else might push them to move forward (or backward)? What happens to this person that gets them to act and begin their adventure? The protagonist clause is really saying, “When something happens…”—what’s the “something”?

We’ll use the novel/movie Jaws, by Peter Benchley, as an illustration how this might play out in execution:

Protagonist Clause: … a fearful, “outsider” Police Chief of a small, coastal vacation town is asked to investigate the possible shark death of a local swimmer …

Here the main character is clear, he is constricted with fear and doubt, and there is a sense of the spark that brakes his inertia, i.e., he is asked to investigate a death.

![]()

Clause #2: Team Goal Clause

Take the next two components of the Core Structure (desire and focal relationship) and combine them to give you the next clause in the premise line.

This clause captures the sense of a tangible want and defines the relationships involved, especially the core relationship (if any) that drives the middle of the story. Now is the time to give a clearer idea of what the main character wants and who is moving through the story with them. This should also give a sense of the motivation for the desire, not just the thing that is desired (i.e., “with purpose”).

Using Jaws, once again, we get the following:

Team Goal Clause: … his worst fears are realized when a marine biologist confirms the cause of death, prompting the Chief to hire a crusty local fisherman to hunt down and kill the beast—forcing the fisherman to take the Chief and biologist along on the hunt …

The protagonist wants to catch the shark and he’s doing it with his team. There is deliberate purpose in this and a clear, tangible goal.

![]()

Clause #3: Opposition Clause

The next two components of the Core Structure (resistance and adventure) combine to give a clear statement about the opposing force acting to upset the story’s applecart.

This is where the writer tries to give a sense of the stakes, the big-picture jeopardy of the adventure, and the central opposing force acting against the character’s action.

For Jaws we have:

Opposition Clause: … only to find himself caught between the town’s greedy mayor demanding a quick kill so beaches can be reopened, and the controlling, resentful fisherman who thinks the Chief is a wuss, and who doesn’t need or want the Chief and biologist on his boat …

The opposition forces are Quint, the biologist, and the Mayor on the human side, and the shark on the non-human side. The opposition is not singular in this story, the way it is in many stories—but it is still unified dramatically. The writer has identified the nature of the “serious pushback” and the chaos that will ensue, including the final outcome if the pushback wins. Here the “opposing force” is defined, as well as the tendency toward disorder, in a clear and dramatic statement that fits perfectly with the idea as a whole.

![]()

Clause #4: Dénouement Clause

The chaos component of the adventure crosses the third and fourth clauses due to the nature of crisis: it spreads and is messy and is often indistinguishable from the resistance it creates and the change it generates. So, in this final combination we see how adventure leads to resolution, the order implicit in all chaos. The last two components of the Core Structure (adventure and change) combine as follows:

Dénouement Clause: … leading to the three men bonding as a team as they battle the monster, where the Chief proves his value and courage, overcomes his fear of the water, and secures his place in the community when he saves the town by killing the beast.

The complexity of the adventure unfolds in the bonding of the men, who have been in conflict throughout, and with the escalating danger from the shark. The final disposition of the protagonist is that he finds his place in this new world he lives in and overcomes his fears. The writer expresses the change that is at the end of all disorder and chaos, as well as the change that is personal to the character from the Protagonist Clause. There is a coming full-circle in a sense; the beginning, middle and end all tie back to the first and most fundamental step of sensing a protagonist and a personal story.

![]()

Step 4: Finalize the Premise Line

This is how the final premise line would look (note the clause identifiers):

Final Premise Line: A fearful, “outsider,” Police Chief [Clause #1] of a small, coastal vacation town is asked to investigate the possible shark death [Clause #1] of a local swimmer, and his worst fears are realized when a marine biologist confirms the cause of death, prompting the Chief to hire a crusty local fisherman [Clause #2] to hunt down and kill the beast [Clause #2]—forcing the fisherman to take the Chief and the biologist [Clause #2] along on the hunt; only to find himself caught between the town’s greedy mayor [Clause #3] demanding a quick kill so beaches can be reopened, and the controlling, resentful fisherman [Clause #3] who thinks the Chief is a wuss, and who doesn’t need or want the Chief or the biologist on his boat—leading to the three men bonding as a team as they battle the monster; where the Chief proves his value and courage, overcomes his fear of the water, and secures his place in the community when he saves the town by killing the beast [Clause #4].

Here you can see the entire structure of the story in a single sentence. Granted, this is a bit convoluted and cumbersome grammatically, but this is a good example of what you end up with after a few initial passes of the process. You can refine as you need going forward. The point is, you have your story, its structure, and a roadmap for writing. It all fits, it all flows and it is a metaphor for a human experience resulting in evolutionary change; it is a story. Armed with this premise line you could confidently move forward to writing pages, knowing your story’s armature was strong.

![]()

Step 5: Test the Premise Line with Objective Readers

Once you think you have a solid premise line, then is it time to start writing? NO! If you’re smart, you’ll “unit test” the premise line.

Find three or four trusted readers who have experience with storytelling, who you respect—maybe even hire a professional consultant—and get their feedback. Your mother is not in this category, unless she is a novelist. You need objective feedback, not hand holding.

Does the premise line work for them? Do they “see” the whole story and get a gestalt picture of the overall structure? Does the idea pull them in? Do they sense the beginning, middle, and end and would they write this themselves if they came up with the idea?

These are just a few of the questions you want them to answer. If you get more passes than thumbs-up, then you have to reassess and decide if you want to move forward with a new idea, or fix this one. If you get a lot of thumbs-up, then you’re probably good to go to begin pages.

![]()

These five steps will help you develop a powerful story premise that can be your early warning system protecting you from story creep and months of lost writing time.

Once mastered, premise development can guide your entire writing process, while giving you an effective and professional pitch tool to use with publishers, agents and editors.

Thanks, Jeff!

About Jeff: Jeff Lyons is a published author with more than 25 year’s experience in the film, television, and publishing industries as a writer, story development consultant, and editor. He is an instructor through Stanford University’s Online Writer’s Studio, and lectures through the UCLA Extension Writers Program, and is a regular presenter at leading writing and entertainment industry trade conferences.

About Jeff: Jeff Lyons is a published author with more than 25 year’s experience in the film, television, and publishing industries as a writer, story development consultant, and editor. He is an instructor through Stanford University’s Online Writer’s Studio, and lectures through the UCLA Extension Writers Program, and is a regular presenter at leading writing and entertainment industry trade conferences.

Jeff has written on the craft of storytelling for Writer’s Digest Magazine, Script Magazine, and The Writer Magazine. His book, Anatomy of a Premise Line: How to Master Premise and Story Development for Writing Success* is published through Focal Press and is the only book devoted solely to the topic of story and premise development for novelists, screenwriters, and creative nonfiction authors. His second book, Rapid Story Development: How to Use the Enneagram-Story Connection to Become a Master Storyteller, is due in 2016. Visit him at www.JeffLyonsBooks.com and follow him on Twitter @storygeeks.

* Amazon affiliate link

Want the Workbook Version? Download our Master Your Premise Line Guidebook here:

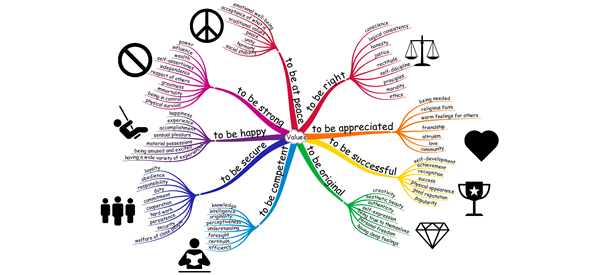

Today’s article is a guest post by story and Enneagram expert Jeff Lyons of StoryGeeks.com. His article touches on a often overlooked aspect of story development that many writers miss and their story structure suffers as a result: their main character’s “moral problem”.

Today’s article is a guest post by story and Enneagram expert Jeff Lyons of StoryGeeks.com. His article touches on a often overlooked aspect of story development that many writers miss and their story structure suffers as a result: their main character’s “moral problem”.